The devoir of a good son is to break the news of surviving a near-fatal miss to his mother softly. Fortune is on his side as it is dusk preventing her from seeing the numerous bandages stuck to his limbs and jaw, torn jeans flapping and a second chin from stitching together the long cut that neatly cleaved the existing one into two.

“Mom, I couldn’t finish my trip.”

“What happened?”

“My motorcycle got jammed.”

“Oh, some engine trouble?”

“Yeah, kind of.”

Revelation gets progressively tough as my jammed motorcycle was actually stuck in a ditch into which it fell skidding off the road after ramming into a car. Luckily somewhere along the horizontal way you and your machine decide to part ways and you plummet down the road emulating the motions of a smart washing machine – tumbling, rolling and spinning all together.

“And you, how are you? Are you okay?” Her voice is raised now, probably suspecting something amiss. A neighbour from far away also peers at me from the balcony she is idling, waiting for my reply. I am dizzy; the brain scan came clean as did the x-rays except the one of my nose but the opioid that was fed me intravenously was taking its toll – I finished the whole contents from a pouch the size of an udder.

That morning right after the accident I gathered myself up off the street trying to be the skookum I always aimed to be under extenuating circumstances: blood rolling down my eyes and nose, mouth and chin, limb joints and hip, my riding jacket looking like a grenade was detonated inside. My head was spinning, and somebody urged me to sit down. Around me passers by milled from whom sympathy emanated in varying degrees. The dizzy spell didn’t last for long, somebody offered me a glass of water which went down tasting tinny with blood. I looked up, like I do these days when I think of my dad. It struck me then that I was actually lucky to be sitting up and not having to be scraped off the street or picked up in parts and gathered into a lungi lent by some perv in the garb of a good Samaritan. The accident kept playing in my head in a slow motion loop: I remembered thinking ‘I am rolling and till now I am fine.’

‘Well, if I stop rolling now, it would still be good as nothing has run over me, yet.’ This crossed my mind three times before I came to a juddering halt by the shoulder of a ditch into which my motorcycle slid and stayed like in the embrace of a long-lost lover. Vehement, snug. There wasn’t space for another, I stayed on the road.

I doffed my helmet expecting a gush of blood like you see in every other page of a manga comic. The mafia boss goes amusedly rhonchisonant seeing my plight from behind dark sunglasses which also reflects the smoke from his cigarillo. The driver of the erring car – he swerved sharply to the right without signal just as I was overtaking him – stepped out holding a baby, I kid you not. I was in high speed alright, heading to Kannur 300 kilometres away for the last Theyyam of the season. ‘The children were bawling hungry,’ he said later when we got to know each other better over bloody-edged cups of coffee. They were out on a picnic, suddenly one of the kids shouted ‘hotel’ and he just turned the car towards it. The last time somebody did this to me I was employed by a leading publication in Kerala, about 20 years ago. Giving two hoots to ramifications, I smashed his windscreen with my helmet, collared him out of the car and was about to do the same thing to his head when a woman co-passenger sprang out and screamed, I think mercy. This time around though I just kept asking him how could be do such a dumb thing and thought about my own drives as a kid in Nigeria with my dad at the wheel.

My dad would pick the prettiest spots if we were packing our own food or the joints that sold the most succulent lamb suya – skewered and smoky, charred mutton slices served with raw tomatoes and onions and freshly squeezed lime juice – with still-warm bread. But clearly he never turned the wheel suddenly anytime; when you are looking at five kids arrayed like tinned sardines on the backseat, the driving becomes nothing short of palmary. Weekends were for cross country travel for VFR. I think in my passing fury I informed the driver he should strive hard that his family doesn’t become statistics along with him.

The highway police came without much delay after I called 100 and gave me a lift till the nearest clinic whose emergency casualty looked like a movie set; I mean, hang a few bananas there and it could pass for a teashop or talcum powder and a barber shop. A nurse began razoring away at my bloodied beard apparently readying me for the stitches – no cleaning, no soaking, no local anaesthesia. She must have been a bad topiarist in her last job. One of my favourite relatives came in the nick of time and with profound apologies to the disinterested staff took me away to a different hospital. First time in my life I didn’t care people seeing me with a bad shave.

Now, the new hospital was a wish come true for me. Ever since I binge-watched Dr House 15 years ago, I wanted to see some good doctors in frenetic action from close quarters. Just the high of seeing some people for whom saving lives was everyday. Imagine if they were to be given Jeevan Raksha or Ashoka Chakra or some other medal for saving lives, they could build whole houses with them. Dr Blesson shifted between a spinal injury victim, an old man whose diarrhoea had become life-threatening, a woman who broke water, a depressive who just didn’t want to leave along with a score of others in beds farther away like a music conductor in concert. Dr Malathy expertly sutured me up across two layers of thick hide after carefully, precisely administered local anaesthesia.

Dr Nandu was the only one with bad news – from the half dozen x-rays he made of most of my body parts, the one of the nose bridge showed a hairline fracture.

“The rest of the pain is just contusion,” he assured me. “Just apply heat and take lot of rest.”

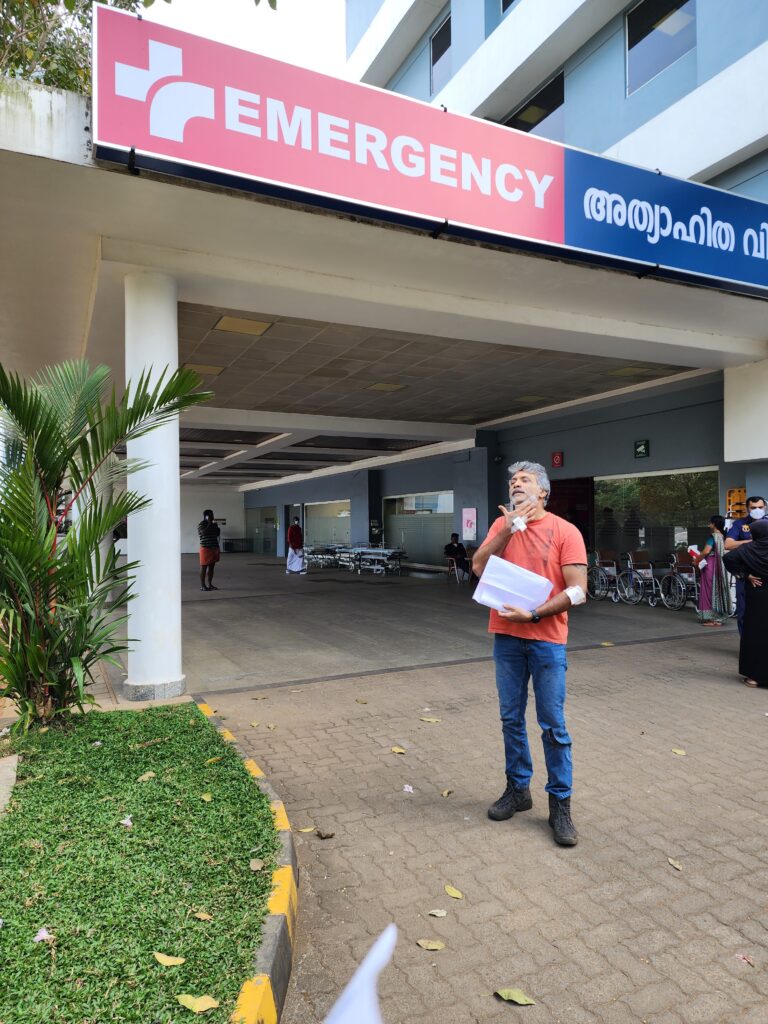

I’m plugging Rajagiri – Probably the only hospital in Kerala where they don’t make you buy meds from the inhouse pharmacy

And then there was Meenu, the ubiquitous nurse. From every curtained station every doctor wanted her for patient information. She was like Android Kunjappan on adrenaline. Besides my own medical history, she was also keen to know the story behind each of my tattoo. Unlike many I had seen in the profession, here was one who genuinely made an effort, cared and wanted to make a difference. Meenu hadn’t eaten for 11 hours but got me coffee in minutes.

A friend picked me up from the hospital and we went directly to the workshop where they had brought my motorcycle in. My baby was another skookum like me – bold face despite thorough battering. Then we went to the police station. They were relieved that I wasn’t filing a case, so it was advice-giving time.

“You must ride motorcycles like ours – they cost maximum ten or twenty thousand rupees and so top speed is thirty or forty.”

“What is the big deal about Theyyam? You can watch Bharatanatyam anywhere.”

And advice-seeking.

“Can you recommend a good coaching centre in Pala for my daughter who is preparing for civil service exams?”

Now, this was good prepping for what was waiting at home.