Daroga Ram raked back with his hand the sparse tuft of white feathery hair repeatedly. Frowns cut burrows across his high forehead. He had no idea what to do: this time the scrimshanking contractor had abandoned work altogether and had vamoosed. The museum that was coming up in the memory of his mother, celebrated folk artist Sonabai, lay derelict in a space cleared next to the family’s fields, amidst sand in plastic sacks split-opened from the impact of careless, hurried stacking. The requisitioned concrete hadn’t reached for over a week which Daroga Ram believes might have been appropriated by the missing contractor. That morning he was at the office of a senior manager with Chhattisgarh handicrafts department to lodge a formal complaint. Protreptic of a timely completion of the project the manager asked him whether mediation by the district collector would work. Daroga Ram didn’t look very convinced about the idea – every prominent person in the locality had intervened in the past too when the contractor had erred in his responsibilities. And since Daroga Ram’s plaintive requests and emotional appeals – himself who was once the sarpanch, village head – fell on deaf ears it was time to take things on a sterner footing. After deciding to file the matter with the district labour court and the desired settlement nothing less than recovering the cost of materials missing from the site and the removal of the contractor, Daroga Ram took time out to tell me about his mother and her village, her art, life and legacy.

Necessity is the mother

It all started many decades ago when Daroga Ram was a toddler. He must have gotten unduly cranky for it was then that the young mother Sonabai realised that there was nothing in the house the little one could play with. Taking a cue from watching either her own grandmother or the village potter during her childhood, Sonabai took a bundle of dried hay and bunched it into a large handful before tying it firmly with strings and inserting four sticks on four sides for legs and binding them into place. A thinner bough was inserted for the tail and a curved stout one for the neck and head. Afterwards she mixed soft clay from the pliable soil next to the well, sieving by hand for stones and leaves, and pressed handfuls of it gently over the straw skeleton giving it a fuller, robust form. She then dried it in the sun hardening the clay, readying it for the rigours of a growing boy’s playmate. Emboldened by the success of her first outing as a toymaker, Sonabai tried her hand at different animals – elephants and tigers and monkeys – and soon enough she was giving form to her favourite gods and goddesses. The artistic inspiration to make the clay toy wouldn’t have possibly come to her as a revelation for a few months earlier she had given shape to her version of the jali or the latticework common in the north, but unseen till then in those parts of central India.

Trying to lull little Daroga Ram to sleep on a hot afternoon, Sonabai noticed how harsh was the summer sun which slanted its way into the veranda flanking the courtyard of their house. The veranda traced its way in a rectangular path which opened to the bedroom, kitchen and the barn. Though there were some plants for shade in the courtyard, the afternoon sun was particularly merciless searing its way through the foliage into the rooms. With a sharp knife Sonabai fashioned a curtain of sorts fastening together crude circular bangles made by tying together bamboo skin peeled from the shoots left behind from their house construction. After hanging this curtain from bamboo poles, supporting it with spliced bamboo stems she had applied soft mud over the latticework. Having thus tamed the sun not just her baby but her whole family slept comfortably. An illiterate her whole life, Sonabai had neither seen nor read about the marble filigrees and latticework which adorned the Mughal masterpieces of north India. What she made that day was wholly the product of her own imagination – a fired up imagination of a mother frantically searching for solutions. While admiring her horse, she had another flash of genius – how about the animals on the lattice? Over the course of the following weeks, Sonabai created the first pieces of an artwork never seen anywhere before: three dimensional bas-reliefs, depicting figures more whimsical than ritual, colourful and playful. A form of art as functional as it was ornamental, an artistic inspiration, an assertion of individual identity. In Sonabai’s case, existence even. For the first decade-and-half of her married life a young Sonabai was kept in virtual isolation by her much older, possessive husband.

The legacy lives

Sirkotga village is 18 kilometres from Ambikapur along Bilaspur highway. Unlike the rest of villages and towns along this route, you will not find mud-baked leviathan trucks ferrying portions of mountains parked by the road that goes through. Instead shady sheeshams and sals line both sides of the road and little boys in smart school uniforms inveigle large bicycles into treading a straight line precariously close to traffic followed by gaggles of school-going girls also in freshly starched and pressed uniform dresses. Altogether you can sense there is something good going for this place, there is purpose in every stride and a gleam in every eye. There is a pervading sense of optimism uncharacteristic of the geographies. In winter many classes other than PT are being held under a comfortable sun in the local village school. Recitals hold the sway in both language and science classes. A couple of kids in the last row are actually sitting, facing the other way, engrossed in well, looking the other way. As i drive into the school compound, everybody turns from the teacher to look the other way; the teacher uses the break to stream out the contents that swelled his mouth. Whatever that chose to remain stuck inside he eggs out with his index finger and spits. But in the building next to the school, the classes are where they are supposed to be – inside classrooms – and the teaching is hands-on.

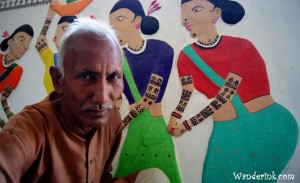

Atma Das Manikpuri is kneeling in the midst of some dozen-odd students; he is showing one how to scrape facial features onto a clay mound, Krishna’s head, while to another he is explaining the right proportions of vegetable dyes for a particular shade of indigo. Atma Ram tells me he was the favourite disciple of Sonabai and attributes all his success as an artist and a teacher to his guru. “I was studying in school when i heard about Sonabai and the international fame she had found from within the four corners of her house.” Hailing from a village about 20 kilometres from Sirkotga, he came to Puhputra village next door where she lived and spent an entire day gawking at the art work she had covered her house with. “Then and there i decided to learn the craft whatever it took,” he remembers. He enrolled in one of the earliest batches which Sonabai taught supported by grants from the central and state governments. “The classes were conducted in the courtyard of her house and she taught us how to sculpt animals and human figures as well make the jali which made her initially famous.”

Obscurity to celebrity

Holi Ram from Puhputra village was 46 years old when he married the 25-year-old Sonabai. He had already been married but had been widowed soon enough. Though a good man and a capable farmer, he came with his own personal baggage; he didn’t get along with the rest of his joint family. Soon after Daroga Ram was born, Holi Ram built a separate hut far removed from the rest of the village and moved in there with his wife and son. Holi Ram also forbade the young Sonabai from visiting her family, talking to anyone, even from stepping out of the house when he was not around. Her imagination obviously bloomed in the isolation imposed and she pursued her newfound passion with a vengeance. Creation kept frustration at bay. She was both master and student; her brushes were chewed shoots and the inks extracts of leaves, flowers, spices and washing bleach. She drew from the visual and the vernacular vocabulary of her own surroundings and whatever limited exposure she had to the outside world till her marriage. Her simple decorative friezes were gradually replaced with her trademark three dimensional sculptures – monkeys crawling up a tree for the fruits, Krishna frolicking with his gopis or the maidens, musicians and dancing women – which were added to the bas-reliefs. Her jalis especially were found to be unique to the entire region which caught the interest of a scouting team from the Bharat Bhavan Museum in Bhopal. The team sawed off the showpiece jali from her house to exhibit at the museum. The public response to the art work prompted the museum to give Sonabai an exclusive exhibition which met with widespread interest as well as recognition of her till-then unrewarded genius. Several national as well as international shows followed and soon enough the Rashtrapati (President’s) Award, given to biggest achievers across fields, came her way.

By then Holi Ram had come around and had allowed Sonabai literally more space. He threw open the doors of his hut to the village, welcomed visitors who wanted to see his wife’s famous jali and other creations and even urged son Daroga Ram to follow in his mother’s footsteps. With more exhibitions sales of their artworks also picked up and both Daroga Ram and his wife Rajenbai began assisting Sonabai. Daroga Ram says that his mother’s success – and the money – from the art has prompted many villagers from the neighbouring areas to appropriate the form without giving due acknowledgment. True, historically women from the region were artists and some were accomplished storytellers and musicians, women also sculpted on walls with clay mythical or figures from history. But her three-dimensional bas-reliefs remain consummate expressions of original thinking, a sparkling testimonial to self-taught artistry where there is no allegiance to established schools, where you draw from your own experiences and beliefs, faith and frustrations.

The home in Puhputra

Sonabai died of a stroke on August 17, 2007. By then she had put her village Puhputra on the art map of the country and abroad. She had taught her craft to several batches of students many of whom who went on to become household names at least in Chhattisgarh. Like Atma Das, who along with another of Sonabai’s students Bhagat Ram, was commissioned to work on the walls of a hospital near Bilaspur; those who have seen it inform me that the art deco these two came up with infinitely cheers up an otherwise sombre atmosphere. Some like Sundaribai who stays next door to Sonabai, have added to the legacy with their own quirky inventiveness and enterprising nature. Daroga Ram, while not busy chasing disappearing contractors, has been trying to make the Sonabai or ‘Surguja’ style of sculpture (named after the district) profitable by addressing its brittle nature by incorporating papier mache techniques.

Driving through a concrete pathway, wide enough for two vehicles, i reached Sonabai’s house in Puhputra; about a kilometre from Sirkotga. Most of the houses i saw on the way had some bas-relief ornamentation; while it has always been so, the practitioners of the art today have been understood to have refined their craft and invented newer styles due to Sonabai’s influence. The sculpting – which is entirely the women’s prerogative – takes place during the time of the construction. Sonabai’s house too is like the rest of them – made with wooden pillars, mud, cow dung, hay and stones. The swept courtyard is visible from the open doorway. Daroga Ram’s son who was chaffing the harvested paddy invited me into the house and i am proudly plied with photographs from Sonabai’s trips abroad, the medals and the felicitations. All around us on the walls i see bright floral motifs, deities, colourful lozenges and animals ‘jumping off’ the latticework – just like how it would have been when Sonabai was around.

The medals are coated in verdigris, some of the trophies are getting rusty and the certificates mouldy. With the family expanding each year, space is becoming premium; the accolades and albums which were in a separate room are now relegated to a corner or stashed away in boxes.

“All the memorabilia associated with my mother will be restored and displayed properly in the museum,” says Daroga Ram.

But at first the labour court palaver.

Acknowledgments

To Daroga Ram who, as luck would have it, walked right into the room where Jitendra Singh, the state handicraft manager, and i were talking about Sonabai.

I have taken some details of Sonabai’s family life from Stephen P. Huyler’s landmark book ‘Sonabai – Another way of seeing.’

Dr Jyotindra Jain’s ‘Other masters: Five contemporary folk and tribal artists of India’ was a source of illumination on the craft.

Sculpt like Sonabai

Atma Das Manikpuri who was a student of Sonabai is a known name in Chhattisgarh and has conducted exhibitions across the country. He has also been teaching the art for over two decades now. When he is not travelling on assignment or exhibition, he can be found at the sculpting workshop next to the primary school in Sirkotga. Many from the village and surrounding areas attend his classes; while most of them are full time students there are some farmers and housewives too who come for a few hours every day. Atmas Das is confident that the art form can be picked by anyone who has the interest and can spare some time.

“The appeal of the art lies also in its simplicity. Once you pick the basics, then the rest is all about your own imagination,” he says. “Like any other art.”

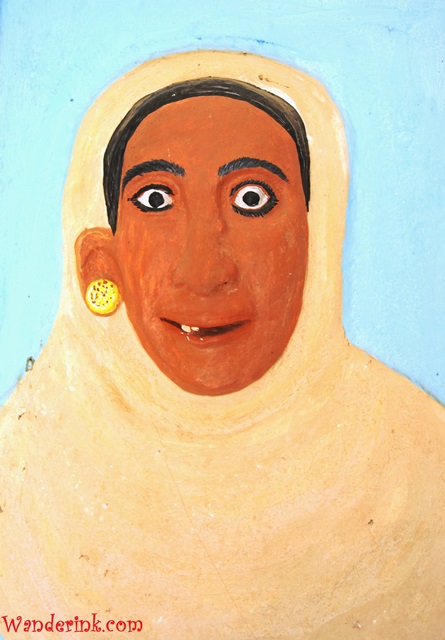

Instead of sculpting on walls, Atma Das uses plywood for practical purposes in his class. The figures are first outlined with a pencil on rectangular ply bases. After daubing the area in glue (in small parts so that it doesn’t dry up), the clay is moulded on it, the facial lineaments and other features are marked with pen knives, blades and other sharp instruments. The wet clay takes an hour to dry afterwards which the rough edges are smoothened out with sandpaper. After giving two or three coating of white, the required colours are applied over it.

You too can learn the Sonabai style of sculpture under Atma Das. Enrol for a full day course at Sirkotga, next to the village school building, 18 kilometres from Ambikapur in Chhattisgarh. The course fee of Rs 500 goes toward raw materials and refreshments. While your mould is drying, you can visit Puhputra, Sonabai’s village, next door and take a stroll around her house, look at the photographs and her artworks. Contact for details: Jitendra Singh, Divisional Manager, Chhattisgarh Handicrafts. Email: jitendra.hsvb@gmail.com Mobile: +91 9425580265

(This course has been developed by Wanderink.com and the state handicrafts department only recently on an experimental basis. There could be the usual initial hiccups in terms of coordination or other logistics which will be addressed the best way possible. Do get in touch with the email above or mail@wanderink.com for any issue you came across.)

Good evening – I am an artist myself and visit India every year. If your courses are still running I would be very interested in attending next year between January and April. I saw some beautiful mud architecture works by Sundaribai at the Serendipity exhibition in Panjim this year and as a sculptor, am fascinated by what is both a simple technique but one that is capable of such complexity in its practice.

Best wishes and regards, Liz Kemp

Liz, the story was written over a year ago. Things change. Better you call up the CTB, the Chhattisgarh Tourism Board, and confirm. They should be able to give you the number of the tourism person in charge of Ambikapur – the nearest big town to Sonaabai’s village.