Romance gets precedence over credence in populist writing. And travel writing is one big pleaser – aiming to pull, pique and prod. Many of the bubbles are what you ‘buy in’ to when you just pass through, fated to burst if you look around a little longer and engage deeper with the locals. So those – is there a TRP for travelogues? – of who throve on populating the Bhangarh Fort with bhoots should script for the Ramsays. Was that pen shaky when you took down those haunting tales? Or were you really scared that you did not take down at all? If you looked back once you’d see them snigger: another bites the bait. On the upside it could even be a life saved. Livestock, mostly.

Let’s drop the soap: Bhangarh’s ‘officially haunted’ tag is an urban legend. Once upon a time tigers used to roam the Aravali range which looms over this hastily deserted township till all of them were poached to feed the rich erectile dysfunction market. As civilisation crept into their backyards they began prowling down the arid, craggy slopes to prey on the habitation below. Stripey hid in the ruins till darkness fell before stealing into fenced-in cowsheds of Rajgarh houses; people or cattle hanging around here after dark made it easy. Today, when tigers have to be airlifted, tranquilised, to the nearby ‘tiger reserve’ Sariska, the ‘haunted’ reputation comes handy for local lads looking for fun in atmospheric settings. About time we moved on from ill-boding sobriquets and looked at Bhangarh for what it’s worth.

A non-ticketed entry could be the heartiest thing the ASI has ever done considering Bhangarh’s popularity especially in the domestic circuit. (But a bunch of locals charge you a couponed Rs 30 for ‘maintaining’ the approach road to the fort – an ongoing endeavour.) You pass by the unmanned gates on the outermost fortification wall – Bhangarh has three of them – and you enter history, albeit a short-lived one. The township lasted just one generation after it was founded in the latter half of the 16th century by Bhagwant Das, ruler of Amer. It was made the capital by his second son Madho Singh, a Diwan (a high official who handles affairs of the treasury) in Akbar’s court; Madho Singh’s elder brother Man Singh was a general in Akbar’s army. An interesting aside: Jodha Bai, Akbar’s much-written-about Hindu wife, was their aunt.

The well-worn granite walkway passes through bazaars and havelis or mansions. A notable one among them is the Dancer’s Haveli where you can still see the remnants of the opera-styled balconies where the nobles would have been seated by the usher before being regaled with mellifluous thumris or graceful jhatkas and matkas in the courtyard below. Intermissions would have been filled up with prestidigitations by an upcoming artist. Inhabiting the remains today are hundreds of langurs and macaques who actually go through very human motions, carnal ones included. A very shaded stretch along the path leads to the 30-foot gates – of more modern origins – of the second fortification wall guarding the fort complex. Inside, from a distance, sits the Bhangarh Fort beckoning to you, with a heartrending crumbly-wrinkly grace, eager for closeness like a neglected grandmother.

Someswar and Gopinath Temples on both sides of the walkway are two very fine specimens of the nagara style of temple design (essentially resembling a tower that inclines inwards). Probably because it was situated on a vertiginous elevation, in an open setting, things were brighter in Gopinath Temple. The Someswar Temple had a, well, sort of eerie air about it. In order to make sure that it wasn’t the legend defining the landscape, I asked around. A local guy whom I had befriended a few days earlier told me travelling tantrics used to hole up in the temple for days altogether and hold some very macabre rituals. Stern measures had to be adopted to oust this wandering ilk and today local lads and law enforcers see to it that things don’t go overboard. Overnighting is overlooked but not burning, well, things. A Nandi sits in the sanctum with his gaze studiously turned away from all these.

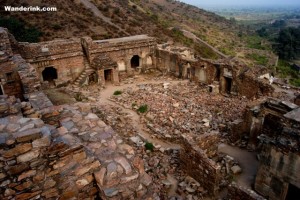

You walk up a ramp into the Fort; what ease considering there used to be three lines of fortifications and five – just five – points of entry on the outermost wall: Ajmeri, Lahori, Phool Bari, Delhi and Hanuman Gates. Inside the fort, you are flanked by elaborate courtyards with connecting doorways, ante rooms with foliated sandstone pillars and crumbling walls with niches for idols and bibelots still intact. Dark passageways down stairways lead to grotty, smelly dungeons. Don’t venture down unless you have a torch as some end abruptly at deep-ended buttes. For the Bhangarh in all its ruined glory climb up to the highest rampart. With the fallen colonnades, massive boulders which once held lofty arches, ornate windowsills and balustrades, from up here it is indeed Acropolis which was also destroyed around the same time as Bhangarh. In fact the scale of destruction begs many parallels: Parthenon, the most important building in Acropolis used to store gunpowder during the Sixth Ottoman-Venetian war, was totalled when hit by a cannonball. In Bhangarh too, the obliteration is of cataclysmic dimensions that theories about its decimation revolve around the supernatural.

The popular ones are that of Singhia and a desi Rasputin, Selu Sewra. Singhia was a local tantric who fell in love with the beautiful princess Ratnavati. He tried to enchant the oil her maid was purchasing from the market so he could seduce her. But the princess came to know if it. She decanted it – probably with some of her own magic – over a rock which rolled over and crushed Singhia. Singhia died cursing the kingdom and all its inhabitants. The very next year there was a war and Bhangarh was vanquished. Selu Sewra was the court magician and healer who tried to seduce the queen with enchanted oil. The only difference here is that Ratnavati is the queen and not the princess. What many consider a more plausible reason is a sibling rivalry between Madho Singh and Man Singh. Man Singh was jealous at the way Bhangarh was flourishing – definitely the way it looked with all the pretty lanes and bazaars and havelis – and charging a false emeute must have unleashed the destruction at his disposal.

Long after the hold of the haunt wears off these are the legends that will go on, probably taking on more gryphon-ic twists. Then even without a fable – or bhoot, for that matter – Bhangarh will still be fabulous.

A delightful read, even though you explained the ghosts (TRPs?) away 🙂

Thank you, Puneet! But you never needed them…ghosts, right!! 🙂 Woof.

Also many thanks for sorting for me Nandi’s gender… always thought it was a she.

Glad to help. Would have been plenty surprised were it a typo, a rarity, in your posts.